A big feast and full bellies are seeping into the minds of most Arcata High students as Thanksgiving break creeps around the corner. The annual event to gather together with loved ones, stuff your faces with mashed potatoes, and avoid political remarks. For some faces at Arcata High, this upcoming break means nothing more than a week off of school.

Growing up in our schools many students recall teachers having them do Thanksgiving activities like coloring hand turkeys, making little construction paper pilgrim hats, or writing what they’re thankful for. These elementary traditions tie down through generations of families celebrating what happened in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1621. Although few students recall learning about any actual history of Thanksgiving.

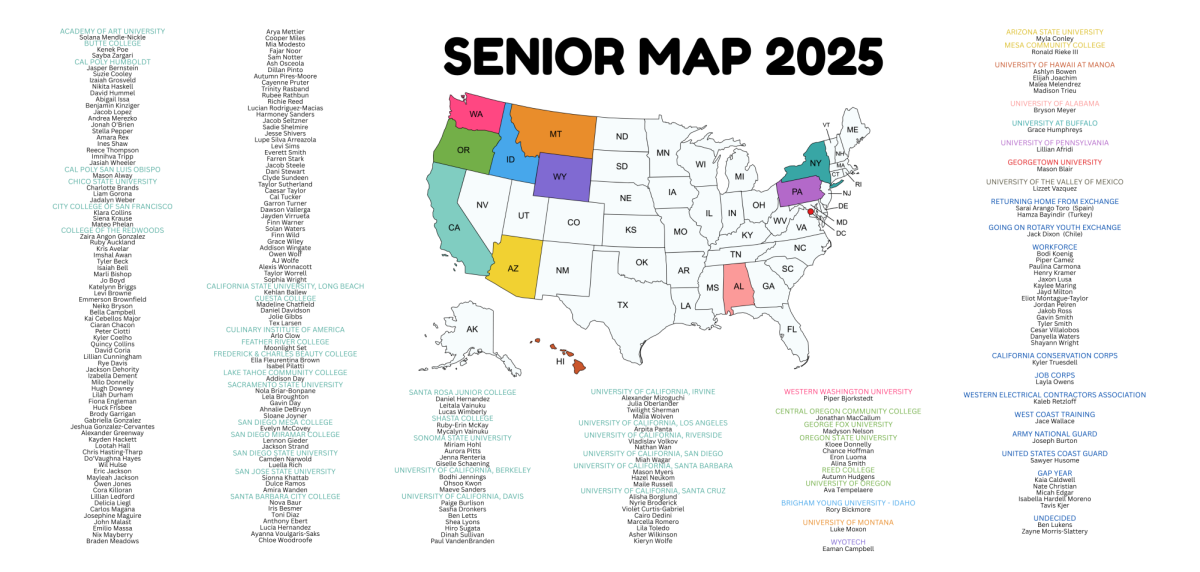

“I don’t remember learning anything about the history of Thanksgiving in school,” senior Eron Luoma said. When asked if he knew anything personally about the history of Thanksgiving Luoma replied, “No not at all. I think we should know more…I’m pretty sure it has a bad history.”

The simplistic version of this annual holiday that many generations grew up learning is merely an extension and continuation of the ideals around Manifest Destiny. The prevailing myth depicts Native Americans—unspecified by tribe—as hospitable figures who welcomed the Pilgrims, taught them how to survive in the New World, shared a meal with them, and then quietly vanished. The false narrative shows Native people supposedly surrendering the land to European settlers, paving the way for the creation of a nation rooted in liberty, opportunity, and Christianity, intended to serve as a model for the world.

“At my school in Las Vegas, Nevada we learned about the Pilgrims coming and standing their ground,” senior Andrea Merezko said about what she remembers learning in school. “Sure [we learned that] it’s a plus to get together with your family and give thanks, but it’s really about the Pilgrims coming, being where they are, and standing their ground.”

In Humboldt County, we’re fortunate to have grown up in an area where it’s not uncommon to learn about our local tribes and the land we stand on despite the amount of misinformation and absence of native voices in our country. Having lots of indigenous influence with land restoration it’s hard to ignore the native cultural aspect of Humboldt County. Most high school or even middle school students could name at least one of our multiple local tribes.

Somewhere on the complete opposite side of the country in Queens, New York is a school called Archbishop Molloy High School. 17-year-old Sharon Kovalskiy shared her experience growing up in an area very different from our own. “I think we should learn more about Thanksgiving in schools. Especially in my schools we were never really taught in depth about any of the Native American tribes or anything in relation to them. They always painted the colonizers in a good light so that’s kinda skewed,” Kavalskiy said.

Though significant culture reintroduction in education has taken place locally over the past 100 years, there are still many instances where native students face discrimination on campus. Senior Evelyn McCovey Native American Club President expressed her shock of others’ words in high school after moving away from her native school in Hoopa.

“During sophomore year this kid in my PE class was talking badly about the natives and saying how Christopher Columbus didn’t steal anything and how this is our [the whites] land,” McCovey said. “That made me feel very dehumanized and down because him and all his friends were laughing and I felt very shamed for my culture.”

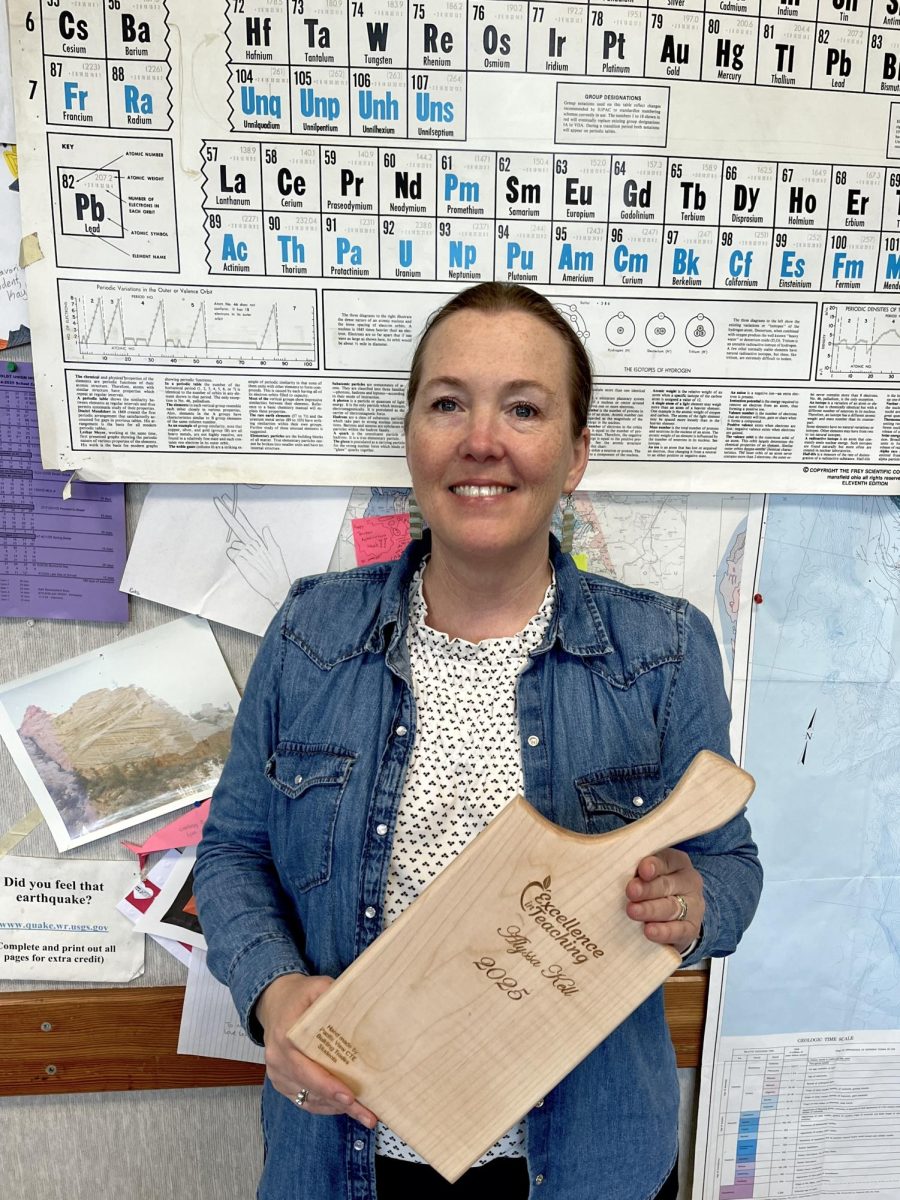

While McCovey was favored with growing up in a school where her culture was appreciated and taught thoroughly, others weren’t. Indian Education Sight Lead for Arcata High, Sheila Richards is upset with the lack of education she received growing up in a different generation.

“It pisses me off now that I was misled and taught stuff that wasn’t relevant, didn’t matter, and didn’t represent the truth,” Richards said. She no longer celebrates Thanksgiving as a way of showing resilience. “When I was 24 in college was the first time I actually learned about the truths and stopped celebrating. I was shocked that I was that old. I was that old when I learned the truth about Columbus. That’s too old to be learning that.”

To learn about the history of the land you call home and acknowledge it on this upcoming holiday is to rewrite the narrative. During Indigenous People’s Heritage Month, the history of the land is especially close to natives on campus.

When the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth in 1620, the Wampanoag tribe’s chief extended an alliance, largely to safeguard his people against their rivals, the Narragansetts. For the next five decades, the relationship was strained by colonial land expansion, the spread of disease, and the depletion of Wampanoag resources. Ultimately, these tensions erupted into King Philip’s War (also known as the Great Narragansett War), a brutal conflict that devastated the Wampanoag nation and irreversibly altered the power dynamics, favoring European settlers. Today, many Wampanoag people mark the Pilgrims’ arrival as a day of mourning, not celebration, recalling the profound losses their ancestors endured.

“Regardless of who you are and where you came from, everyone needs to be educated on the truth [of Thanksgiving],” Richards said.