After more than a century of being dammed, the Klamath River now runs freely from Upper Klamath Lake in Oregon to the Pacific Ocean. The removal of the dams has been discussed for over 20 years, but only in November of 2022 was the project approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Holding the title of the second-longest river in California, the Klamath River runs about 257 miles from Oregon to Northern California, emptying into the Pacific Ocean. Starting in 1918, four dams were put into place along the river to provide flood control and hydroelectric power to the region. These dams were named Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, J.C. Boyle, and Iron Gate. In late August of this year, Iron Gate – the final dam remaining – was removed, allowing the river to return to its natural state.

Although the dams generated hydroelectric power and created local jobs, damming the Klamath produced generally negative outcomes for the environment and those who rely on the river. Some of the main issues with damming the Klamath included taking away the river’s natural characteristics, creating ideal conditions for the growth of toxic blue-green algae, and raising water temperatures downstream. Of all the organisms in the river, the salmon were impacted the most by higher water temperatures and changes in river conditions. The Klamath is home to mainly Chinook and Coho salmon which serve a key role in the area’s watershed. The populations of salmon in the river were at risk due to years of rapidly declining population numbers. As a result, a federally mandated salmon restoration plan was put into place, further complicating plans for the dammed Klamath. In the early 1900s, Coho salmon were abundant in the Klamath basin, however, they are now considered a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Their populations began a sharp decline due to hydraulic mining, fishing, water diversions, and the construction of the dams on the river’s tributaries. The construction done on the river prevented salmon migration and polluted the waters with additional silt. Through undamming the river, the natural condition of the watershed will be on track to being restored, hopefully increasing salmon population numbers.

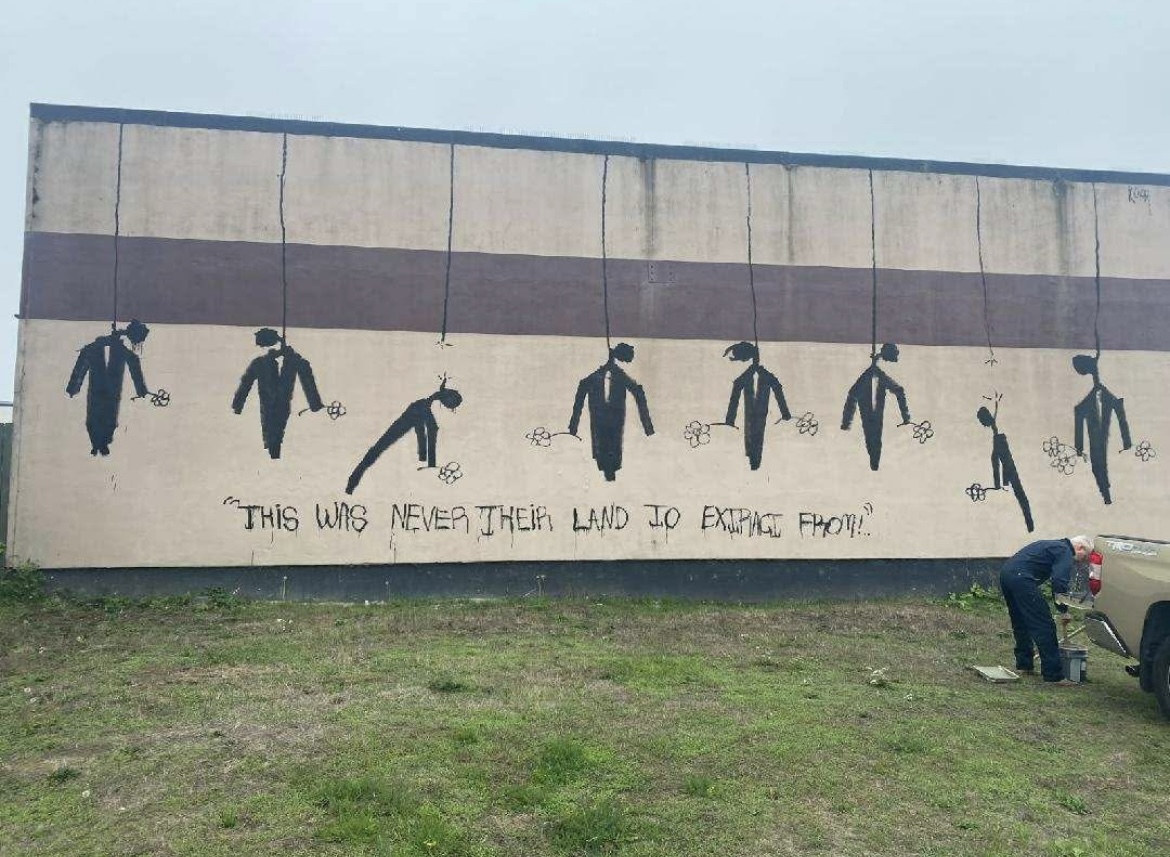

The river, as well as the salmon in it, are very important to the local Native American tribes. The Klamath River passes through many tribal territories, including the Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Shasta, and Klamath homelands. This river has always held significant meaning to the members of these tribes, providing food, transportation, and other vital resources to the native people.

Last year, students in Arcata High’s Native American Club learned about the dam removal on the Klamath through the Blue Lake Rancheria, a local tribal agency. The Rancheria provided paid internships for students and allowed them to visit the Klamath Dam sites as a capstone to their internship.

Arcata High School’s Native American Club advisor, Sheila Richards, shared details about the trip.

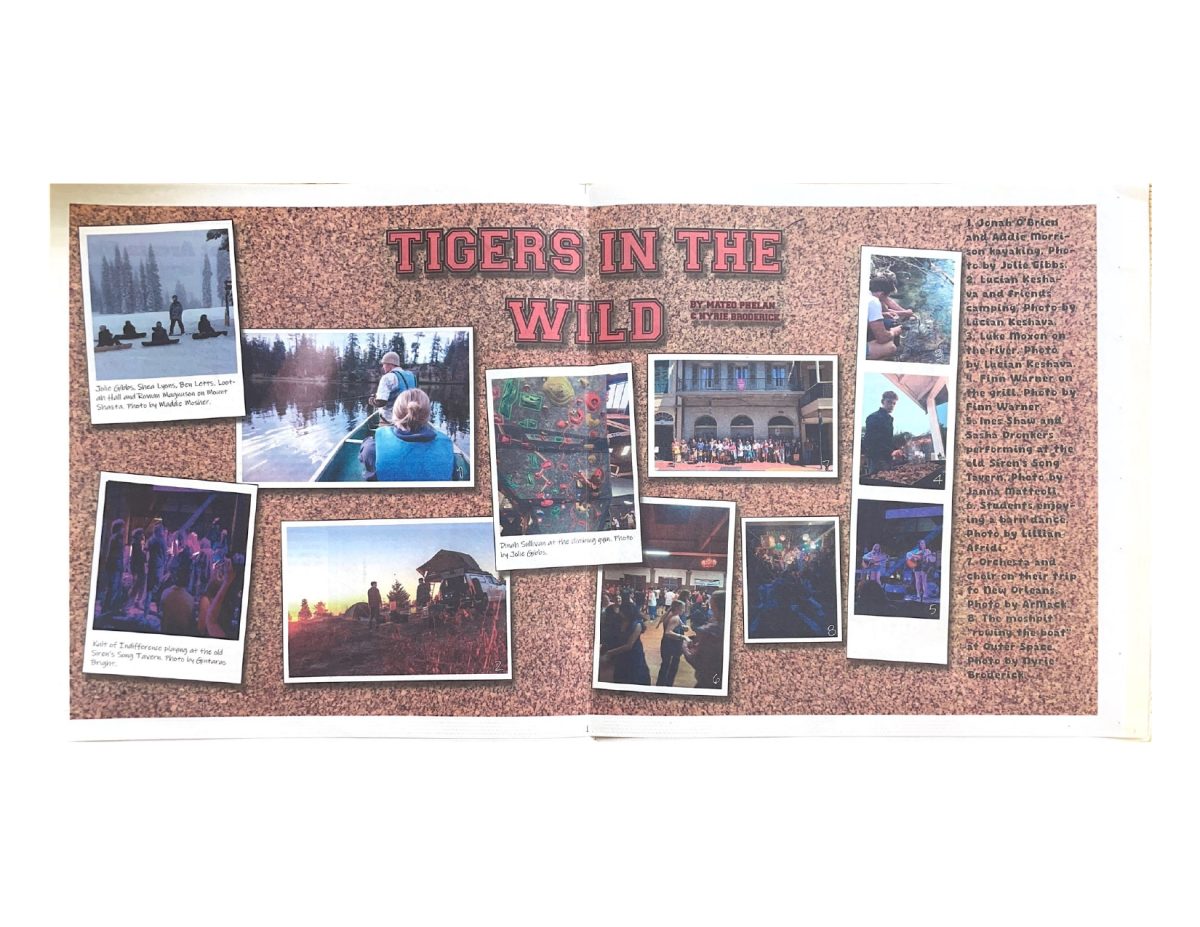

“They toured the dam removal, and then they toured the reservoir, went swimming, horseback riding, and camping,” Richards said. “They also participated in workshops where they got to walk around the ground of the reservoir. It was interesting because when the water was removed it created these cracks, a foot wide; they got to experience the transitions that the dam and the reservoirs will go through.”

This trip, open to members of various tribes in the area, was highly beneficial to educating people about the Klamath River and the state of the dams. Two of the three AHS students who went on the trip were sophomore Alia Loyola and senior Imnihva Tripp, both members of the Native American club on campus.

“It was fun to take a trip without my parents and meet new people,” Loyola said

The program pulled numerous students from high schools such as Eureka, Fortuna, and McKinleyville, as well as parents and families from the Northern California Indian Development Council. By demonstrating to the community what changes the river has undergone, more people can be aware of the effects of damming rivers.

When talking to Tripp and Loyola, both touched on the experiences they had while they were there. “We got a tour,” Tripp said. “There was this crazy area that this guy took us to, [at] his house, we got to make food there and he showed us this dried-out river.”

The area in question was the reservoir ground, where the water had recently dried up when the dam had been removed. This experience allowed students at our school to understand the changes that this watershed underwent and the impacts that large-scale hydroelectric dams can have on a river and the ecosystems downstream. After years of man-made influence on our river, it will take time to heal the Klamath. However, removing the dams is one step (or four) in the right direction for a healthy river, watershed, and ecosystem.