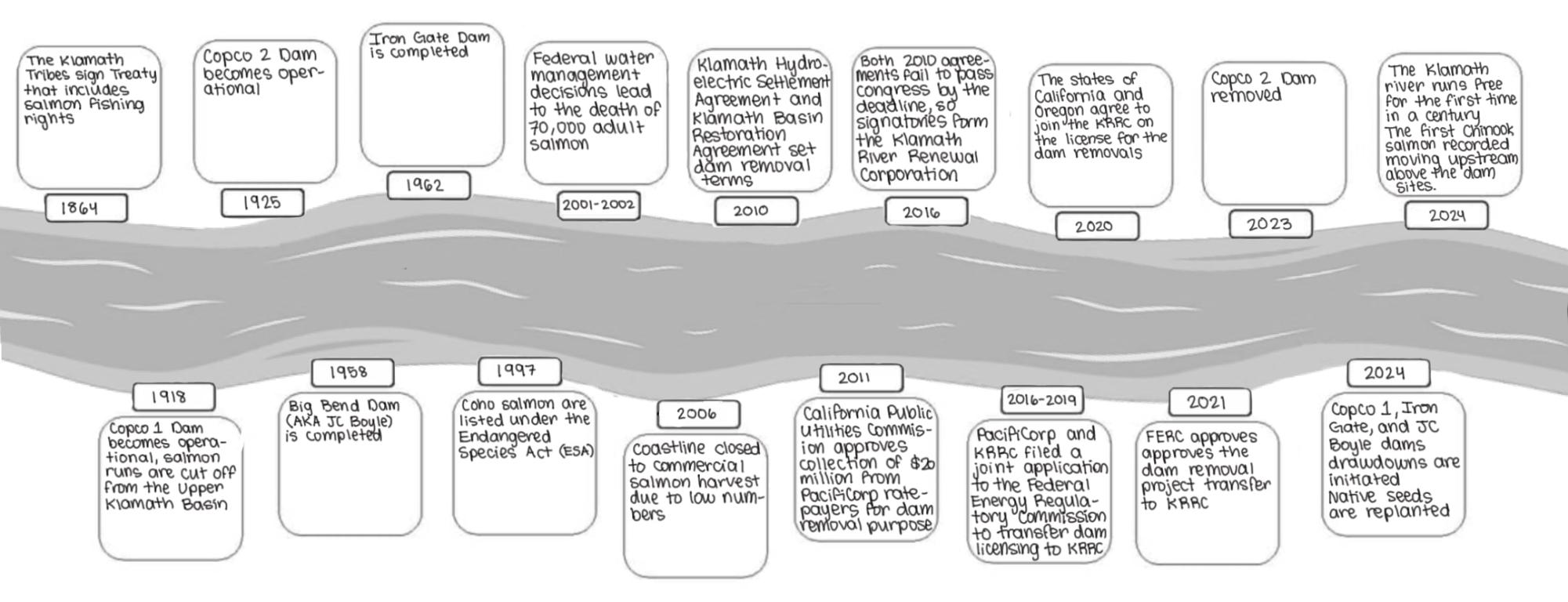

Growing up in Humboldt County, the Klamath River dams have always created a buzz of conversation in our community. Over the past few years, significant strides have been made to remove these four large hydroelectric dams. After over 100 years of these operations running, the first salmon have been monitored entering the upper basin of the Klamath to breed.

Fish are tracked by scientists by placing radio telemetry devices on them, and their locations can be seen and studied to monitor restoration efforts and their impacts. During the spring season, there is a lot of sediment running down the river, and salmon numbers are hard to count as a result. There is no official count of the population released at this time.

Over 400 miles of the salmon’s natural habitat are now accessible. However, the removal of these dams will not revitalize the salmon population magically. Time is needed for the salmon stronghold in the upper basin to return, and there is still a lot of work to be done.

“It seems like there’s just not enough water for fish to be able to have a full recovery, and also for farmers to continue to be diverting at the rates that they have been doing, which has steadily increased over the years,” said Amber Jamieson, Water Advocacy Director for the Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC).

A big part of Jamieson’s job as Water Advocacy Director is to meet with different coalition groups, which brings her very close to the projects on the Klamath. Meetings with tribes, scientists, environmental non-profits, the Department of Water Resources, farmers, the waterboard, and different agencies bring the perspectives, wants, and needs of many different people together.

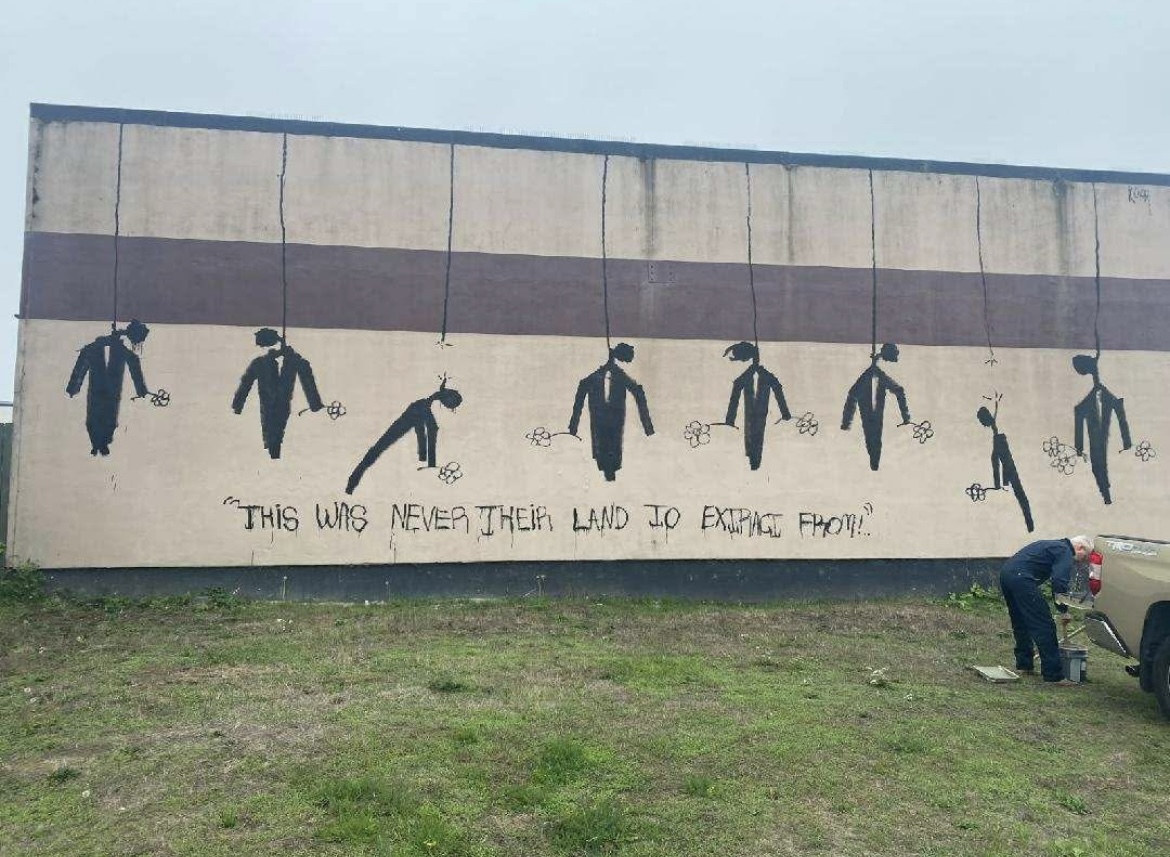

“We’re thinking about a farmer who’s complaining that they’re making $3 million a year, instead of $5 million a year, and comparing that with a whole entire tribe of people who are suffering from not even being able to feed their families at all. They’re not asking for a profit. They’re just asking to exist,” Jamieson said.

The Native communities surrounding the Klamath have been facing the negative consequences of the output of the river for centuries due to European settlers. In The Effects of Altered Diet on the Health of the Karuk People, Kari Norgaard, Ph.D, wrote, “The loss of the most important food source, the spring Chinook salmon run, is directly linked to the appearance of epidemic rates of diabetes in Karuk families. A high percentage of Karuk people continue to fish and hunt traditional foods; however, over 80% report that they are unable to harvest enough to meet their family needs.”

The issues on the Klamath run deeper than just monitoring the fish and water; the balance of priorities between communities is where many problems lie.