Juan-Antonio Santisteban’s background goes beyond being multicultural; with his brightly colored shirts, beaded wooden necklace, and enthusiastic use of the “shaka”, may at first seem more of a surfer dude than the new Arcata High Dean. Not only is he highly qualified for the position, but Santisteban brings understanding and empathy to the table when interacting with students.

On his father’s side, Santisteban is Afro-Peruvian. He discusses the 2017 recognition of the Northern Peruvian city, Zaña, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This area holds a rich history; one can still find Spanish ruins dating back to Peru’s colonial era. Zaña was settled by indigenous groups long before Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 1500s,

motivated by gold and silver in the Andes. They brought with them enslaved African peoples to mine precious metals, subjugating the local population as well. Spanish reign was fatefully ended with a mammoth flood in 1720; washing away Spanish profit and buildings, it left the indigenous Andean in- inhabitants and the now freed Afri- can population. Over generations, these groups created a distinct Afro-Peruvian culture. UNESCO’s recognition of Zaña is a monumental change, as explained by Santisteban, “You don’t get funding, you don’t get nothing if you’re not on the census, not recognized by the government.” This was a marked step towards the visibility and preservation of a unique Afro-Latino culture.

Santisteban is also Mexican, and his mother is from Guadalajara. The city is recognized as a cultural center; along with being the capital city of Jalisco, Guadalajara is the birthplace of mariachi and other cultural icons. Among other places, Santisteban has lived in both countries he traces his background to.

Santisteban recognizes how his background has impacted his worldview. Diversity is key, he said, and compares communities to forests. In wild areas, you would be hard-pressed to find a dominant species of vegetation. Applying this to education, it’s easy to show there’s no set mold every student should fit into, and Santisteban shows just how important it is to accept and, “meet people where they’re at. When you respect someone, […] you invite the person’s culture to come into play. And for us, culture is everything: it’s how you eat, it’s how you talk to people. So having that diverse culture helps me connect with the variety that exists in the world and the student body.”

Santisteban didn’t begin his working life in education. He originally worked alongside much of his farmer family (himself studying soil microbiology), in the Moche Valley, where Zaña is located. During this time, Santisteban fought with the choice of staying in agriculture, “I was at the pivotal point of my life,” he said, “Where I was still making the decision that like, do I have to do one thing the rest of my life?” Two of the biggest inspirations for his change in paths were his mom and wife. He describes watching his mom pursue a multitude of paths, while his wife was the one to suggest a teaching career. “I was just like me? A teacher? No way, like, I’ve been cleaning toilets and washing dishes, like, blue-collar jobs, man. I had no reference for that right?” In this regard, Santisteban reminds students to stay “open to the journey.” His educational and administrative journey began in California in 2011. Santisteban’s first position was a STIP (full-time, single site-based) substitute teacher, or as he declares it, “A ‘go for’ dude,” Working nearly every position for two years, whether in the cafeteria, office, or teaching, he declares that’s when it clicked, “I realized, I think I can do this.”

Santisteban recounts his time working in a Title One school in the Fruitvale district of Oakland. Many students in these schools fall into the bottom socioeconomic range, and these schools subsequently receive Title One federal funding to help meet their needs. Santisteban specifically chose to work in these schools, hoping to show students hardships don’t dictate their lives. “In Latino America, poverty isn’t seen the same way as in North America…”

“It’s seen here as almost a disadvantage, but in Latino America, it isn’t – you’re still motivated, not down about it.” He did his best to transmit these values, showing students the opportunities ahead of them, “Of course, there’s cloudy days, but like, let’s see if we can help you get where you need to be, even if it’s cloudy out.”

Students have noticed that Señor Santisteban keeps a laid-back attitude as opposed to an authoritarian style. He approaches the role of Dean as a customer service position, “I want to work at people just as if they were coming into a restaurant, like dude, I’m gonna be your server today.” Santisteban values the human journey, elaborating, “You start noticing that change takes time, people grow, and you can assist them by contributing to their positive aspects.”

Santisteban spearheaded the implementation of a new tardy policy; surprisingly to many students, the sweeps aren’t about discipline, but rather understanding. He restates the importance of meeting people on their level, “As I’m being dean already for the first couple weeks, dude, we’re helping a lot of kids, and a lot of families, who wouldn’t necessarily be asking for help. But because they got caught in the tardy sweep, or they got caught doing something, and I’ve gotten a chance to meet with them, then that’s where the conversation opens up. You’re not gonna be tripping on attendance if you’re tripping about like, ‘there’s nothing to eat at my house’.” The sweeps are his “safety net”, allowing him to identify students with unmet needs. “If we can be that lighthouse of hope, why not?”

Moving aside from school life, Santisteban discusses his two greatest loves, Nature (his wife) and nature (Mother Earth). “I know this is gonna sound like a trip dude, but some of my best friends are trees.” Even before he and his wife moved to Humboldt, they had been visiting the Avenue of the Giants for over a decade. One of the main differences between city life

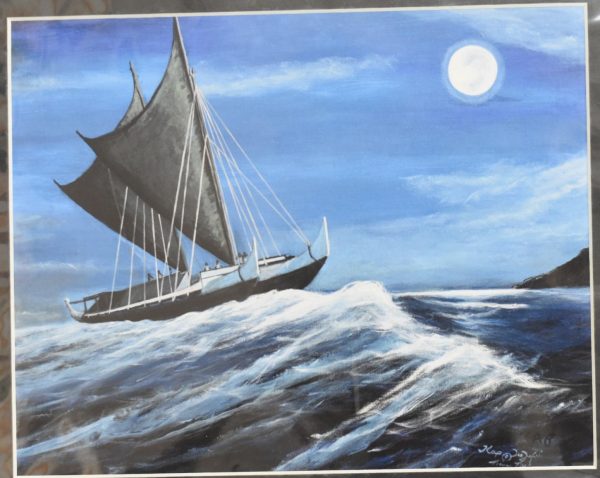

Finally, Santisteban tells the story of meeting the artist KAP. After spending time together, he was given a painting entitled “Eddie Would Go”, about which KAP de- clared, “I didn’t know I had painted this for you until I met you today.” It tells the story of a brave man named Eddie, who valiantly went out to sea during a storm to answer a fisherman’s distress call when no safety crews would. “When I see the students, the fact that you came to school regardless of whatever problems you have in your life, that’s the courage to go, like Eddie would go,” Santisteban said. “You may come from who knows where, but the fact that you’re here, that’s the respect I immediately have on everyone. Because it’s like, you’re here dude, I’m here. Respect.”